This post appeared in the, "Ask The Cheesemonger" section of this week's E-ssue of our newsletter, "The Grapevine." It is a dynamic article in that I've been updating as the passion takes me!

Q: Why are cheese names so confusing?

A: Uhm, you lost me!

Q: There're European ones that sound like towns - Gruyere, Cheddar. Then there're the funky random ones that sound like beers - Billy Blue, Constant Bliss, Bloomsday...

A: Ah, etymology! "What's in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet." Yes, that is the William Shakespeare Rose, left.

When many people first delve into growing their knowledge of fine cheeses, figuring out the names of cheeses is something that drives us nuts! Our brains are hard wired to look for context, a definitive frame of reference by which to judge new experiences. Most of us do not like to operate in gray areas. The world of cheese, if you forgive the analogy, operates in nuances of gray. Embrace them!

As part of our ongoing web site upgrade project I’m designing a ‘Virtual Cheesemonger’ to guide you through our online store. I don’t want to give too much proprietary information away, but the basis of our Virtual Cheesemonger is a classification of cheese. Where does one start? Texture? Origin? Variety? Milk Type? Production Method? All of the above!

Old World cheeses are generally named after the region or method of production. Open a good cheese atlas* at random and browse the famous varieties of cheese such as Parmigiano Reggiano, Gorgonzola, Manchego, Reblochon de Savoie, Roquefort, Emmental, Comté, Stilton, Cheddar, the list goes on… New World cheeses, while based on more famously named European cheeses are generally named after the farm on which they originated, often appended with a whimsical name with great meaning for the cheesemaker. For example, Cato Corner Farm Bloomsday. Alternatively, New World cheeses may receive a whimsical name alone. Consider, Consider Bardwell, if you will!

{* I like the "World Cheese Book" edited by Juliet Harbutt,

Dorling Kindersley Penguin Group (UK), 2009}

Let’s look at Old World cheeses as our illustration. There’s a joke in the artisan cheese world. We say, “Would you like a story with that (cheese)?” I’m unsure where this originated, but in a nod to the Slow Food movement, I think it suggests something antithetical to the eponymous, “Would you like fries with that?” Some of these cheeses are easy to spot why they’re so named. Others, not so much! What they all have in common, however, is that there is always a good story behind the cheese, and isn't that what good food is about? Sharing stories, community, if you will?

Gorgonzola. I always assumed that there was a gorge involved. I grew up in South Wales overlooking the ‘West Country’ – the origin of Cheddar. Sunday afternoon car trips often ended at Cheddar Gorge. Before my editor freaks out, I should state, more accurately, that our Sunday afternoon car trips ended at the car park, adjacent to Cheddar Gorge! These trips forever marked my frame of reference for cheese! By the way, does anyone remember the Canadian animated series, “Bob and Margaret?” My favorite episode was the one where the couple entertained Canadian guests just a little past their guest sell by (stay by) date. Margaret fantacized about pushing her Canadian guests over Cheddar gorge. I digress! Gorgonzola – originally named, “Stracchino di Gorgonzola” derived from the Italian word, stracca, meaning tired. Gorgonzola was made in the fall when the cows returned, exhausted from mountain pastures to the meadows of Lombardy, where Gorgonzola was the main trading town. Easy!

Manchego. Not my favorite of Spain’s many cheeses, but easily the most famous. Named after the dry plateau of La Mancha in the center of Spain. The Moors named this region Al Mansha (land without water). It is the landscape that comes to mind when I think of Spain: hot, arid, dry. Such land is suited for sheep pasturing. It is the specific local breed of sheep, Manchega, that help give Manchego its name.

Reblochon de Savoie. You can be forgiven for thinking this stunningly beautiful, rich, buttery, washed rind, raw cows milk cheese is so named because it's from the (Haute) Savoie region of France. Why? You're half right! You see Reblochon has been made in the summer Alpine pastures of the Haute Savoie since the thirteenth century, but was unheard of until after the French revolution. Why? The name Reblochon comes from the old Savoie word reblocher, meaning, "to re-milk," or, "to pinch the cow's udder again!" Up until the French revolution the farmers were taxed according to the volume of milk their cattle produced. Farmers were forced to milk their cows in the presence of the tax collector. To avoid paying the tax, the farmer would only partially milkthe cows while the tax man was there. Once he'd left, the cows were re-milked. The remaining milk was much higher in fat and was reserved by the family for personal cheese making. After the revolution the tax was removed.

Roquefort. Folklore aside (2000 years ago love struck shepherd leaves his bread and cheese lunch in a cave while romancing, and returns to find it covered in a greenish mold), Roquefort, the most sublimely delicious sheep milk cheese EVER (think you don’t like blue cheese, put down that dressing and get thee to a cheese shop NOW), has been aged in the limestone caves of Cambalou, Southern France for centuries. In 1411, Charles VI signed a charter granting the people of Roquefort-sur-Soulzon the right to make Roquefort cheese. In a testament to terroir and the perilous way many of our traditional foods cling to existence, the specific strain of bacteria naturally occurring in the caves of Cambalou are also named for the cheese they help produce: penicillium roqueforti. All of this story telling does however have me stuck in a chicken or egg mind trap. What came first, the village, or the cheese? Easy or not? I’ll let you decide!

Emmental. Ah, the great melting cheese. I’m not going to cover its famous cousin here. Gruyère has a somewhat obscure, and very confusing, if fascinating etymology. Reasons of brevity cause me to walk on by, and well, “You know how to (Google), don’t you, Steve?” Emmental, or Emmentaler, traces its origins back to 1293. However, the name was first recognized in 1542 when the recipe was given to the people of Langehthal in the Emme valley.

Comté. Produced for centuries in the region of eastern France known as, “Franche- Comté.” Could it be that easy? Yes, until you consider its alternate name, “Gruyère de Comté.” OK, I’ll stop teasing. Gruyère is purported to be named after the town of Gruyères in Switzerland. Sounds plausible until you consider that Gruyère also refers to the forests in Charlemagne’s Holy Roman Empire (which covered what is now France, Switzerland, and parts of Germany), over a millennium ago. Charlemagne’s men sold the forest wood to the local cheesemakers to fire the kettles they used to cook the curd for the cheese we know as Gruyère. Easy, non?

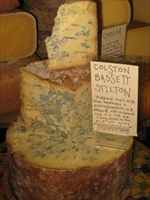

Stilton. Pop Quiz - named after the town in which it was made, or the town in which it was first sold? During the early eighteenth century, the town of Stilton was a staging post (town used to change/rest horses along the roads connecting major towns) on the London to York road. Cooper Thornhill, the landlord of the Bell Inn in Stilton, began serving a local soft, blue-veined cheese made in the neighboring town of Melton Mowbray (also famous for its Pork Pies also granted PDO - Protected Designation of Origin, by the European Union), Leicestershire. So you see, Stilton was in fact named after the town in which it was popularly sold, and not the town in which it was made. If it had been the reverse, what would have been the name of the famous Melton Mowbray Pork Pie? I once broke a tooth on a pork pie while on a childhood camping trip. Not a lot of people know that! The PDO control of Stilton means only three counties in England may produce a cheese called Stilton. I carry the Colston Basset variety. Yum!

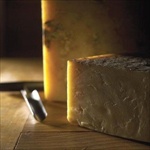

Cheddar. I left the most complicated one until last! Easy when you consider that Cheddar originates from the village of Cheddar, in Somerset, South West England (AKA, “The West Country”). Cheddar Gorge (mentioned above), is on the outskirts of Cheddar village, and contains a number of natural caves, which provided the ideal humidity and constant temperature for maturing the cheese. Cheddar cheese traditionally had to be made within 30 miles of Wells Cathedral. Easy when you consider that the name Cheddar also refers to the curd-cutting technique of repeated cutting and stacking, and draining of the curd blocks necessary to produce this type of cheese – “Cheddaring.” Not so easy when you consider that in the domain of name protected foods (pun intended!), tragically, the name Cheddar was never protected. As such there are as many types of cheese named cheddar as there are ways to categorize (and hence name) cheeses! More in fact! Consider also that the history of Cheddar - a cheese that is very much part of the old world, is intimately tied up with cheeses in the new world American colonies. Cheddar etymology is very complicated! The European Union has designated a PDO (Protected Designation of Origin – a name protection) of, “West Country Farmhouse Cheddar” to denote cheddars that are made in a specific region of England that remain true to the historically accurate method of cheddar production and the resulting cheese. This type of cheddar is rugged, bound in lard and cloth, with many fissures where mold intrudes from the rough rind. This is the cheddar seen on medieval banquet tables! This type of cheddar is oft returned to the cheese shop because it is moldy! The history of Cheddar is a fascinating, complicated tale worthy of a PBS special. I shall return to Cheddar as an article in its own right. I also eagerly anticipate the release of Gordon (Zola) Edgar's new book on Cheddar, due out in 2012.

Now we turn back to the new world – the Americas (all apologies to our Antipodean friends!). The development of cheese production in the Americas is closely tied in with the colonies and with the expansion of settlement in the emerging country, together with the great cheeses of the old world. I will return to this in a separate article on Cheddar. For our purposes here, I will broadly claim that in order to understand our rapidly evolving numbers of American artisanal and farmstead cheeses, we firstly need to acknowledge the work and role of the American Cheese Society. Please visit their website and join this very important organization. Our enjoyment of fine cheeses in the USA is due to their efforts over the past thirty years. Also support independent cheese shops whom are members of The American Cheese Society. Ask them!

So, in brief I will say in order to understand naming of new world cheeses, firstly seek to understand the main types of great old world cheeses since our American cheeses are mostly based on some type of great old world cheese. This is a generalization of course. To the credit of The American Cheese Society’s work, American cheeses are evolving quickly. For now, at least it still helps to consider which type of old world cheese the American cheese is based on. Steve Jenkins' 1996 book, "The Cheese Primer" contains one of the most complete sections on, "The Great Cheeses" of the (old) world (pages 473 - 517). Another frame of reference, as I mentioned above, is that often the name of the individual farm, or dairy, is prefixed to the name of the new world cheese. A third frame of reference is the quirky pattern of naming the cheeses after the personality traits of the cheesemaker. Cato Corner Farm in Connecticut has some fine farmstead cheeses with an equally high caliber naming convention – cheesemaker Mark Gillman's love of James Joyce.

Congratulations, we made it to the end of the article. How're you feeling? Overwhelmed? Tired? Confused? Enlightened? Hungry? In conclusion, my advice when it comes to understanding, heck, remembering, cheese names, is the same as I give to the panic stricken new hire at the cheese counter. Find a frame of reference that works for you. For me it’s as much about geography as it is methods of production. Use that as your yardstick, and work your way out from there, tasting indiscriminately as you build your own mind map! Use the tools available to you: books, articles, Google, and so forth. Rehoboth Beach Cheese Company’s Virtual Cheesemonger tool in development now will help guide you through methods of classifying cheese based on texture, milk type, country of origin, suggested use, and so on. What’s that if not a naming convention?

Andy Meddick, for the Rehoboth Beach Cheese Company.

0 comments:

Post a Comment